In light of the recent media coverage of the domestic violence case involving Ray Rice (see NYT) of the N.F.L., please find a recap of helpful information regarding this topic below.

REBORN INTO THE LIGHT by Maria Iskakova

Over 100 people gathered in Millbank Chapel at Teachers College, Columbia University last October to engage with a panel discussing themes of gender and culture around domestic violence. Panelists and attendees wore purple, creating a visible display of solidarity and community.

We once again would like to honor this event and remember that upcoming October is Domestic Violence Awareness Month. More resources can be found at the bottom.

Please read our experts remarks along with some staggering statistics below (view full Prezi presentation here).

World Health Organization (WHO)

The WHO named Violence Against Women (VAW) a global health problem of epidemic proportions. There are many different types of VAW, but intimate partner violence (IPV) is the most common. VAW occurs in all countries and communities with varying prevalence rates (15% to 71% of women between 15-49 years old). This variability shows that VAW is preventable.

U.S.A.

- 1 in 4 women experiences violence by a current or former spouse/boyfriend at some point in her life.

- Battering is #1 cause of injuries for women-- more common than rapes, muggings and automobile accidents combined.

- An act of domestic violence (DV) occurs every 15 seconds.

- 20-24 year olds are at 3 times the risk.

- 1/2 of all marital relationships involved some form of DV (pregnancy & motherhood are risk factors, not protective factors!).

- 40% of mass shootings in past 3 years started with a gunman targeting a female partner.

- 70% of deaths happen after a woman leaves (stalking may continue even after abuser is remarried; or woman must continue to face long and arduous child custody battles).

- DV is chronically under reported (so these are likely underestimates).

New York City

Of the 683 homicides in 2012, 58% were of females (>16 yrs) killed by an intimate partner (IP); compared to 3% of males homicides killed by IP. Of the 119,355 total assaults last year, 80% were female; 27% (31,911) were committed by IPs. In NYC it is now a Class A Misdemeanor to strangulate someone-- a common DV related injury that used to be difficult to prosecute. Thanks to Article 121 - NY Penal Law - 2,003 individuals (94% men) were charged in first 15 weeks it took effect.

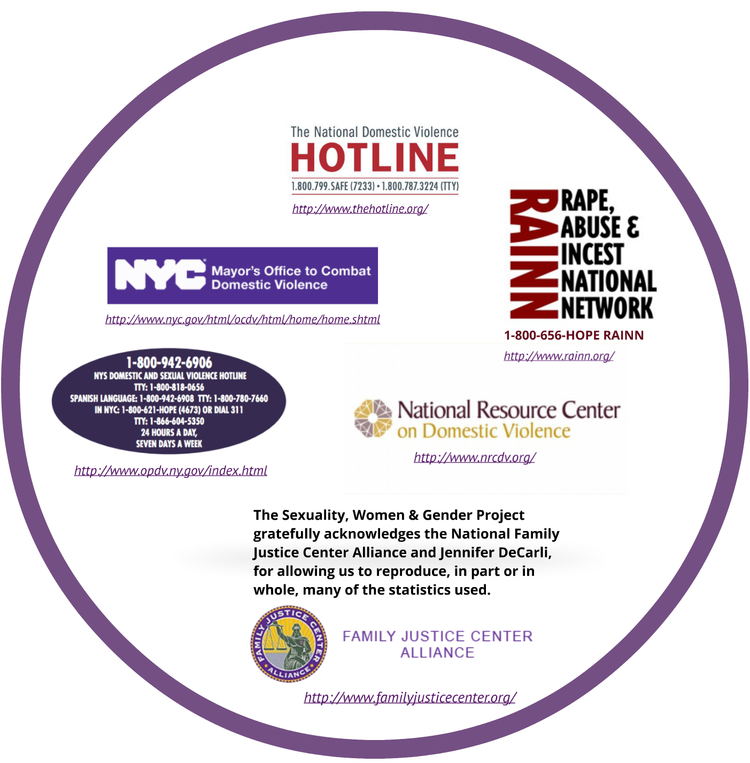

To see more statistics visit the Mayors Office to Combat Domestic Violence or the New York State Office for the Prevention of Domestic Violence.

The panel was moderated by Dr. Aurelie Athan, a co-founder of The Sexuality, Women, and Gender Project. She framed the conversation by naming domestic violence as a public rather than a private issue for its consequence of severely limiting human potential for society. Panelist Sethu Nair, the Manager of Communications & Outreach at Sakhi, an anti-domestic violence organization working with the South Asian population of New York, brought this point home by asking the question, "Who in this room has experienced abuse or knows someone who has?" Almost every hand in the room was in the air.

Discussing domestic violence as an extreme form of gender inequity, the panel raised the question: What do we really mean by Domestic Violence?

At its core it is about power and control. Whether emotional, physical, or sexual, these abusive behaviors are used by one person in a relationship to control or overpower the other. As written and defined, abuse is non-gendered, nonspecific, and open to possibility: partners may be married or not, gay or straight, old or young, men or women, living together, separated, or dating. However, women are usually the victims of DV and usually present with the most severe cases, with male victims reporting incidents of stalking, online stalking, or threats to their new partners more often than physical violence.

Leslie Morgan Steiner: Why domestic violence victims don't leave. [video]

Abuse was characterized as a pattern of behavior as well as a mentality, reflective of the psychological potential in each of us-- whether on the giving or receiving end. Those on the receiving end of abuse carry the greatest burden and are at risk for death, physical injuries, unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, substance abuse, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental disorders. Despite these sobering realities, the panelists highlighted the positive narratives of victims of gender-based violence who go on to become survivors, advocates, and activists.

Panelist Jennifer DeCarli, a lawyer turned social worker, is employed by the Mayor's Office to Combat Domestic Violence where she is the Executive Director of the New York City Family Justice Center in Brooklyn. Her vast experience representing victims of domestic violence in Family Court and directing the center provided the panel with a wealth of information about the lived experience of victims of domestic violence and their families. Ms. DeCarli believes that Family Justice Centers act as the best practice model for addressing issues of intimate partner violence because they provide victims with a host of resources to suit their varied needs all under one roof. The room went silent when she expressed that 70 to 100 clients come through the doors of her center each day. She mentioned that individuals unacquainted with DV often ask her:

"Why don’t victims just leave?”

She finds this question endlessly frustrating and explained that her clients may have trouble or choose not to leave an abusive relationship for many pragmatic as well as emotional reasons; these reasons include but are not limited to housing, children, finances, immigration status, and love and loyalty. Jennifer also stressed that the victim actually finds herself in the most danger during the period directly after leaving the abusive relationship. In cases where victims do choose to leave, housing is often the most pressing issue. According to New York state law, a victim may only remain in a domestic violence shelter for 180 days.

Stephanie Basilia Spanos, a psychiatrist for families and children, also sat on the panel, emphasizing the developmental toll that domestic violence takes on children. She brought attention to the pervasive themes of DV in children's literature, including Cinderella, Harry Potter, the Brothers Grimm, and Oliver Twist. In her work, Dr. Spanos often encounters the harmful narrative of domestic violence as a “private matter” or “family secret;” she explained that children are the last members of the family to report domestic violence because they are biologically adapted to protect the family that serves them. Tragically, she often confronts cases where abused children suffer learning problems, emotion dysregulation, alteration of the physical brain, and traumatic brain injury, a harm that most often occurs in the context of war. Children are often the witnesses of DV and may finally be the ones to call 911.

Panelist Yi-Hui Chang, the former Assistant Director of the New York Asian Women's Center, spoke about the stress this work places on case managers who often suffer from insomnia, burnout, compassion fatigue, and PTSD symptoms (vicarious traumatization) after listening to these extreme narratives of human suffering. She also brought attention to the unique conflict facing immigrant victims, who often wish to leave an abusive relationship without involving the criminal justice system but who paradoxically cannot file for an independent visa without a criminal justice report. Asian immigrants also experience pressure to not only preserve the reputation of their families in the United States, or host country, but also to preserve the reputation of their families in their home countries of origin. She spoke of the complex constellation of domestic violence within some collectivist cultures whereby it is not just the partner who may be abusing the woman, but also the in-laws and other extended family members. When asked how a woman might “extract” herself from such situations, she clarified that this is not the right word or approach to use, as most women, regardless of cultural background do not wish to lose complete ties with their loved ones no matter how violent the context—emphasizing that affiliation and family bonds may be as important to a woman as her own personal safety.

The panelists explained that gender-based violence is difficult to detect from outside of the relationship as there is no profile for the "typical abuser" or "typical victim." In fact, domestic violence is an issue affecting women from all walks of life regardless of age, race, religion, socioeconomic status, and educational attainment. Furthermore, the early signs that abusive dynamics have entered an intimate relationship are often subtle and even hard to detect by the victimized partner. For example, possessive behaviors often begin as seductive behaviors, with the abuser presenting as an especially attentive, present, and available partner. However, these behaviors can later become distorted, as this affection turns into a pattern of control-- rendering the victim’s world smaller and more isolated as a result of encroachment by the abusive partner's need to have power over every last detail. Victims describe that physical abuse often manifests for a period of time but then stops because, "a look is all you need to know you have to control your behavior."

How does a woman arrive to the moment of naming these behaviors as abuse? Yi-Hui Chang answered that a line becomes crossed that the victim can no longer tolerate and that this line is specific to each individual. We each have a line that we don't know we have, until we do. During her journey to leaving an abusive relationship, a woman often finds that it is much more difficult to get divorced in New York, for example, than it is to get married. Counseling in the form of practical guidance and advocacy might be better in the beginning and more exploratory therapy of the traumas experienced are recommended after the case has been stabilized. Yi-Hui Chang also illuminated the presence of IPV in the lives of LGBTQ couples. She often saw cases in which the abusive partner threatens to out the sexual identity or past gender identification of the victim in the workplace or social circle.

While the panel brought awareness to the many grave realities surrounding domestic violence, it also shined a light on the potential to reverse these trends through public policy, cultural awareness, education, and services, like those provided to survivors by the expert panelists, countless other professionals, and the organizations they support. Sethu Nair particularly emphasized the power of our legislative and advocacy force and the need for more innovative approaches that bring awareness to the community directly through creative activities such as dramatic plays or women’s circles of support. She emphasized that culture is not only to blame but can be a resource as well. Cultures are not monolithic and have people with varying beliefs across a spectrum. Creating allies within a culture and starting to change the minds of others is how mindsets shift.

In the end the panelists embodied the kind of diverse orientations and support services a person struggling to make sense of domestic violence will need: legal, psychological, social, legislative, psychiatric, etc. This model for wrap-around services is the cutting-edge of domestic violence interventions we have today. To find a Family Justice Center near you if in New York City, to find national domestic violence resources, or to find out how to get help or volunteer, see our resources below.

To find out about the co-sponsors of the evening, including the organization A.G.A.P.W, and detailed biographies of the panelists, please click here.

Lastly, this event also served to host the official launch of The Sexuality, Women & Gender Project. The SWG Project has three aims: to promote pedagogy, produce research, and to apply what is learned in the field. It will be providing a certification and concentration through the MA program and will continue to organize events open to NYC. More information about the project can be found at www.swgproject.org.

By Laura Curren

![Leslie Morgan Steiner: Why domestic violence victims don't leave. [video]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51e5c3ffe4b07ebd69cedd73/1410374548211-S2LVDL7V3A78JG8VRJ7H/image-asset.jpeg)

![Let's Talk About It: Domestic Violence. [video]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51e5c3ffe4b07ebd69cedd73/1410374643722-P7W8WS4SSA9ZOWMUFSV2/image-asset.jpeg)